Byte Endianness in computers has been a constant source of conflict for decades. But is there really a clear advantage to one over the other? Let’s explore together!

Origins of the Term

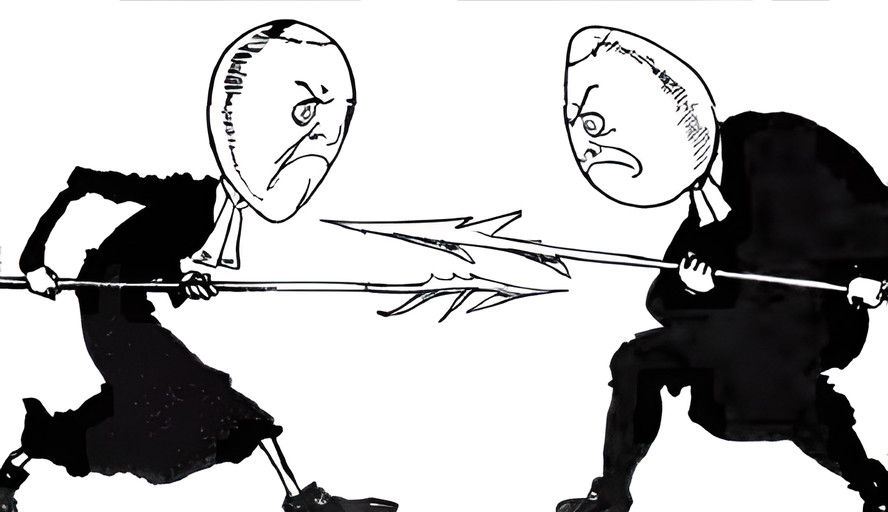

The terms “Little Endian” and “Big Endian” originate from Jonathan Swift’s 1726 novel “Gulliver’s Travels”. It tells of long strife culminating in a great and costly war between the empires of “Lilliput” and “Blefuscu”, because they disagreed about which end of a boiled egg to break for eating. The “Big-Endians” went with the Emperor of Blefuscu’s court, and the “Little-Endians” rallied to Lilliput.

The terms were adapted for computer science in 1980 by Danny Cohen in an Internet Experiment Note titled “On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace” , describing the conflict over the different ways of arranging bits and bytes in memory as components of larger data types. For byte-oriented data, “Little Endian” places the least significant byte of the value at the lowest address, and “Big Endian” places the most significant byte at the lowest address.

| +0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Endian | 0xDE | 0xAD | 0xBE | 0xEF |

| Little Endian | 0xEF | 0xBE | 0xAD | 0xDE |

Both approaches have their adherents, and many flame wars erupted as rival CPU architectures, data formats, and protocols jockeyed for supremacy.

Origins of the Concept

The most common argument for big endian ordering in computers is that it matches the “natural order” for writing numbers. This makes it easier to read numbers in a hex dump, and is less of a cognitive load overall when humans are looking at the encoded data. But how exactly did this “natural order” come about?

Origins of our Numbering System

Our modern numbering system has its roots in the Hindu numbering system, which was invented somewhere between the 1st and 4th century. At the time, there were competing writing systems that went right-to-left and left-to-right, with right-to-left being favored where the numbering system we inherited was created. It therefore was convenient for numbers to also be written right-to-left.

The Hindu numbering system further developed into the Hindu-Arabic decimal system around the 7th century and spread through the Arab world (right-to-left was also the dominant style there, and so this convention was kept). It was adopted into Arab mathematics by the 9th century, and then introduced to Europe via North Africa in the 10th century.

Although many writing directions developed in parallel (left-to-right, right-to-left, top-to-bottom), the Hindu-Arabic visual order was always preserved (high digits on the left or top, regardless of script direction) in order to prevent confusion as globalization took root. So if your script direction was right-to-left, you wrote numbers in little endian order, and for all others you wrote them in big endian order.

You can see some vestiges of the little endian origins in the German language: “ein und dreißig” (one and thirty - 31). By the time larger numbers become commonplace, the transition to the big endian way of saying numbers was already underway, making for some confusing word patterns: “neunhundert ein und dreißig” (nine hundred, one and thirty - 931).

Thus, our concept of “natural” number endianness turns out to be a cultural artifact resulting from a backward compatibility issue when applying a right-to-left numbering system to a left-to-right or top-to-bottom writing system.

Consequences of Endianness on a Numbering System

What happens when a culture adopts a particular endianness for writing numbers? Let’s have a look.

Consider the following list of numbers in our current way of writing them in a left-to-right writing system (big endian):

1╔═════════════════════════════════╗

2║ 1839555 ║

3║ 84734 ║

4║ 67526634 ║

5║ 495 ║

6║ 2 ║

7║ 20345 ║

8╚═════════════════════════════════╝

9 ⬆

10 "Ones" digit

The numerals here are ordered the way we expect them to be ordered: with the most significant digit on the left and the least significant digit on the right. All of the numbers need to be aligned along the “ones” digit so that they can be easily compared.

To write such numbers in a left-to-right system, we must first estimate how much room the digits could take, and then pre-emptively push to the right so that our “ones” column can remain aligned vertically.

Notice how I had to use a preformatted section with a monospaced font so that I could add a bunch of spaces to align the numbers properly!

In a right-to-left writing system, the “ones” digits would be aligned along the margin (to the right) and would grow outwards (left) into the free space (which is why ledger pages are arranged this way).

1╔═════════════════════════════════╗

2║ 1839555 ║

3║ 84734 ║

4║ 67526634 ║

5║ 495 ║

6║ 2 ║

7║ 20345 ║

8╚═════════════════════════════════╝

9 ⬆

10 "Ones" digit

To better visualize this, observe the numerals with digit endianness reversed for left-to-right readers:

1╔═════════════════════════════════╗

2║ 5559381 ║

3║ 43748 ║

4║ 43662576 ║

5║ 594 ║

6║ 2 ║

7║ 54302 ║

8╚═════════════════════════════════╝

9 ⬆

10 "Ones" digit

In this way of writing, “594” represents “five and ninety and four hundred”.

Notice how the “ones” digits naturally align to the left margin. There’s no need to pre-emptively space anything; just write the numbers, no matter how long they get.

Everyone remembers the hassles of doing long multiplication, right?

1╔═════════════════════════════════╗

2║ 2 4 1 6 5 ║

3║ × 3 8 4 1 ║

4║ ─────────── ║

5║ ║

6╚═════════════════════════════════╝

Before you even start, you have to think about how much room you’ll eventually need, because if you get it wrong you’ll end up running into the left margin:

1╔═════════════════════════════════╗

2║ 2 4 1 6 5 ║

3║ × 3 8 4 1 ║

4║ ─────────── ║

5║ 2 4 1 6 5 ║

6║ + 9 6 6 6 0 ║

7║ + 1 9 3 3 2 0 ║

8║ + 7 2 4 9 5 ║

9║ ───────────────── ║

10║ 9 2 8 1 7 7 6 5 ║

11╚═════════════════════════════════╝

But what if the numbers were written in little endian order?

1╔═════════════════════════════════╗

2║ 5 6 1 4 2 ║

3║ × 1 4 8 3 ║

4║ ─────────── ║

5║ 5 6 1 4 2 ║

6║ + 0 6 6 6 9 ║

7║ + 0 2 3 3 9 1 ║

8║ + 5 9 4 2 7 ║

9║ ───────────────── ║

10║ 5 6 7 7 1 8 2 9 ║

11╚═════════════════════════════════╝

Now suddenly it’s no problem. The empty space is to the right, and the numbers also grow to the right! Instead of fighting the writing system order, numbers now flow with it.

So while everyone of course considers their culture’s number endianness to be “natural”, there is a distinct advantage to writing numbers in little endian order. And in fact, that’s the way they were first invented!

So What?

What does this have to do with endianness in computers? We don’t have “space to the right” to be mindful of, so none of the arguments about number endianness in meatspace would seem to apply to computers at first glance. But computers and data formats do have characteristics that endianness can take advantage of.

Endianness in Computers

When dealing with computers, matching endianness to our way of visualizing numbers would be argument enough if the decision were otherwise arbitrary. Even if our system is backwards, keeping things consistent between computers and the more dominant left-to-right scripts is at least a small advantage.

So what exactly are the advantages each endian order enjoys in computing?

Advantages

Detecting odd/even

With big endian order, you need to check the last byte. With little endian order, you check the first byte.

1Big Endian: 8f 31 aa 9e c2 5a 1b 3d

2 ^ 3d is odd

3

4Little Endian: 3d 1b 5a c2 9e aa 31 8f

5 ^ 3d is odd

Advantage: Little Endian

Detecting sign

With little endian order, you need to check the last byte. With big endian order, you check the first byte.

1Big Endian: 8f 31 aa 9e c2 5a 1b 3d

2 ^ 8f has sign "negative"

3

4Little Endian: 3d 1b 5a c2 9e aa 31 8f

5 ^ 8f has sign "negative"

Advantage: Big Endian

Recasting a pointer

Recasting pointers involves interpreting a memory location as different types. For example, taking a memory location that contains a 32-bit integer and recasting the pointed-to value as a 16-bit integer. Recasting pointers isn’t very common in higher level languages, but it happens often in compilers and assemblers.

With big endian order, you must adjust the pointer’s address to match the beginning of a different sized type. With little endian, a recast degenerates into a no-op.

1| Big Endian value 1 | Little Endian value 1 |

2| | |

3| +0 +1 +2 +3 +4 +5 +6 +7 | +0 +1 +2 +3 +4 +5 +6 +7 |

4| | |

5| | 32 bits | | | 32 bits | |

6| 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 | 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |

7| | |

8| | 16 bits | | | 16 bits | |

9| 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 | 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |

Advantage: Little Endian

Arbitrary precision numbers and arithmetic

Arbitrary precision numbers (aka big integers) are composed of integer elements in an array, which allows computing with values greater than the largest discrete integer type. Nowadays, the most common discrete type used for big integer arrays is uint32 or uint64.

1| u64 | u64 | u64 | ...

The first element contains the lowest 64 bits of data, followed by the next higher 64 bits of data, and so on (little endian ordering). The reason for this is because, as carry values spill over, it’s simply added or removed from the next element in the array.

If the elements were ordered big endian, you’d have to do a bunch of shifts and masks to correct everything whenever a carry occurred. The more array entries are in play, the more correction operations you’d have to do. You also have to shift everything over whenever the number grows bigger (basically the computer equivalent of shifting the whole number over when we run out of left-margin space on paper).

Although this scheme can be realized with either byte order, there is an extra advantage to little endian byte ordering: If the CPU is little endian, you wouldn’t even need to care about the element size in the array because the bytes would naturally arrange themselves smoothly in little endian order across the entire array. Thus you could perform arithmetic using a single byte-by-byte algorithm, regardless of the actual element size (some little endian CPUs even have special multibyte instructions to help with this).

| Ordering | Element 0 | Element 1 | Byte-by-byte? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big | b7 b6 b5 b4 b3 b2 b1 b0 | b7 b6 b5 b4 b3 b2 b1 b0 | No |

| Little | b0 b1 b2 b3 b4 b5 b6 b7 | b0 b1 b2 b3 b4 b5 b6 b7 | Yes |

Advantage: Little Endian

Arbitrary length encodings

Arbitrary length encodings such as VLQ allow for lightweight compression of integer values. The idea is that integers most often have the upper bits cleared, and so they don’t actually need the full integer width in order to be accurately represented.

VLQ uses big endian ordering, which works fine when representing values up to the maximum bit width of the architecture, but once you start storing larger values that would require big int types, you run into problems:

For simplicity and real estate given this blog format, let’s assume a CPU with a word size of 8 bits, but the same concepts apply to bigger word sizes too. To store larger values, we use a big int type, which requires arranging the words into an array in little endian order. Since VLQ is encoded in big endian order, the first chunk marks the highest bit position, and we work our way down from there.

First chunk (continuation bit “on”, so more chunks coming):

1 W0 Bits W1 Bits

2| 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 | 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 |

3| H6 H5 H4 H3 H2 H1 H0 | |

For the next chunk, we need to shift the high bits over into the next element to make room for the next set of bits (sound familiar?).

Second chunk (continuation bit “off”, so this is the end):

1 W0 Bits W1 Bits

2| 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 | 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 |

3| H0 L6 L5 L4 L3 L2 L1 L0 | H6 H5 H4 H3 H2 H1 |

Shifting across only one element required:

- Copying W0 to W1

- Shifting W1 right by 1

- Shifting W0 left by 7

- Logical OR next 7 bits from the next VLQ element into W0

And this gets worse the more elements are in play.

Now let’s see how it would work if the data were encoded using LEB128 (basically the same thing, but in little endian order):

First chunk (continuation bit “on”, so more chunks coming):

1 W0 Bits W1 Bits

2| 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 | 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 |

3| L6 L5 L4 L3 L2 L1 L0 | |

For the next chunk, we split the value across two elements.

Second chunk (continuation bit “off”, so this is the end):

1 W0 Bits W1 Bits

2| 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 | 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 |

3| H0 L6 L5 L4 L3 L2 L1 L0 | H6 H5 H4 H3 H2 H1 |

Splitting the last VLQ element required:

- Logical OR W0 with (element«7)

- Copy (element»1) to W1

And this remains at constant complexity no matter how many elements are in play.

Bonus: It’s also possible to do arithmetic in LEB128 while it remains encoded!

Aside: Did you notice how disjointed it looks listing the high bits to the left in a left-to-right system? It would have flowed much better were they listed this way:

1 W0 Bits W1 Bits

2| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

3| L0 L1 L2 L3 L4 L5 L6 H0 | H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 |

Advantage: Little Endian

Variable length encoding with a prepended length field

A common encoding trick is to reserve a few bits of the encoded space to store the length of the field (low bits of the low byte if little endian, high bits of the high byte if big endian).

1(XXXXXX LL) (XXXXXXXX) (XXXXXXXX) (XXXXXXXX) ...

2 - or -

3(LL XXXXXX) (XXXXXXXX) (XXXXXXXX) (XXXXXXXX) ...

Generally with this encoding pattern, the two bits LL represent the total size of the data.

Example:

| LL | Bytes | Data Size |

|---|---|---|

| 00 | 1 | 6 bits |

| 01 | 2 | 14 bits |

| 10 | 4 | 30 bits |

| 11 | 8 | 62 bits |

If this data is encoded in little endian byte order, the decoding routine is pretty easy:

- Read the first byte and extract the length field.

- For each byte to be read:

- Read the byte into the current position.

- Increment current position by 1 byte.

- Shift the result right 2 bits.

You can simply decode the whole thing and then shift the decoded value two bits to the right because the size field is always in the two lowest bits of the value, regardless of the size.

If the CPU is also little endian, the algorithm gets even simpler:

- Read the first byte to extract the length field.

- Read the same address again using the correct sized load instruction (recasting the pointer).

- Shift the result right 2 bits.

If the encoding used big endian order, the length field would be at the top of the high byte, which means that you’d need to mask out a different part of the decoded value depending on the data size.

Advantage: Little Endian

Convention

Most network protocols and formats until recently have been big endian (Network Byte Order).

Advantage: Big Endian

“Naturalness”

Binary dumps look more in line with how humans with left-to-right scripts expect to read numbers.

Advantage: Big Endian

Sorting unknown uint-struct blobs

If you have a series of unknown blobs, and know only that the internal structure has only unsigned integers stored in descending order of significance, you can sort these blobs without knowing what the actual structure is.

Yeah, that’s a pretty rare thing, but technically it’s an advantage, and someone, somewhere is using it!

Advantage: Big Endian

Conclusion

The big endian advantages tend to be cosmetic or convention based, or of minor usefulness. The little endian advantages offer real world performance boosts in many cases (given the right algorithm or encoding to take advantage of it).

Big Endian Advantages

- Detecting sign

- Convention

- “Naturalness”

- Sorting unknown uint-struct blobs

Little Endian Advantages

- Detecting odd/even

- Recasting a pointer

- Arbitrary precision numbers and arithmetic

- Arbitrary length encodings

- Variable length encoding with a prepended length field

The biggest advantages go to little endian because little endian works best with “upward-growing” data (meaning data whose bits cluster to the low bits and grow into the upper empty bits). An example would be integers, which use higher and higher order bits as more digits are needed. And since integers are the most common data type in use, they offer the most opportunities.

Big endian ordering works best with “downward-growing” data. An example would be floating point, which in some little endian architectures is actually stored in big endian byte order (although this practice is not very common due to portability issues).